Share

14th November 2018

06:31pm GMT

The football alliance between north and south was a tenuous one over the previous 40 years. Belfast was the stronghold of Irish football at the time and teams from the north had been dominant.

The Leinster Football Association felt that the Irish Football Association was biased towards clubs and players in the north-east of the country. The final straw for them came when the association arranged an Irish Cup semi-final replay between Glenavon and Shelbourne to be played in Belfast rather than Dublin.

They said they did so because of security concerns, as this was during the War of Independence. Down south, Leinster were furious and broke away to form their own association - the Football Association of Ireland.

So, on its base level, the reason that there are two national teams is that there are two associations. There are two associations because of a dispute from almost a century ago that no longer holds any relevance for football on the island.

The football alliance between north and south was a tenuous one over the previous 40 years. Belfast was the stronghold of Irish football at the time and teams from the north had been dominant.

The Leinster Football Association felt that the Irish Football Association was biased towards clubs and players in the north-east of the country. The final straw for them came when the association arranged an Irish Cup semi-final replay between Glenavon and Shelbourne to be played in Belfast rather than Dublin.

They said they did so because of security concerns, as this was during the War of Independence. Down south, Leinster were furious and broke away to form their own association - the Football Association of Ireland.

So, on its base level, the reason that there are two national teams is that there are two associations. There are two associations because of a dispute from almost a century ago that no longer holds any relevance for football on the island.

Almost 100 years later, this small island is no longer capable of hosting two competitive international teams. It is time to pool resources, to create a single international team to represent the island of Ireland. There are more reasons to do so than there are arguments against it.

Football is an outlier on the matter. Irish athletics, rugby, hockey, basketball, cricket - almost every major international field and team sport - represent the entire island of Ireland.

Almost 100 years later, this small island is no longer capable of hosting two competitive international teams. It is time to pool resources, to create a single international team to represent the island of Ireland. There are more reasons to do so than there are arguments against it.

Football is an outlier on the matter. Irish athletics, rugby, hockey, basketball, cricket - almost every major international field and team sport - represent the entire island of Ireland.

Of the Irish footballers that migrated to play in England between 1976 and 1985, 50 played in the top-flight. Between 2006 and 2010, just nine of the 67 Irish players who went to make a career in England made an appearance in the top flight.

Last weekend, just six Irish-born players started in the Premier League - Shane Duffy (Brighton), Matt Doherty (Wolves), Seamus Coleman (Everton) and Greg Cunningham (Cardiff City). While Northern Ireland's Jonny Evans started for Leicester City and Craig Cathcart started for Watford.

At this declining rate, how many Irish-born players will be featuring regularly in the Premier League in 10 or 20 years' time?

Of the Irish footballers that migrated to play in England between 1976 and 1985, 50 played in the top-flight. Between 2006 and 2010, just nine of the 67 Irish players who went to make a career in England made an appearance in the top flight.

Last weekend, just six Irish-born players started in the Premier League - Shane Duffy (Brighton), Matt Doherty (Wolves), Seamus Coleman (Everton) and Greg Cunningham (Cardiff City). While Northern Ireland's Jonny Evans started for Leicester City and Craig Cathcart started for Watford.

At this declining rate, how many Irish-born players will be featuring regularly in the Premier League in 10 or 20 years' time?

However, in the 24-years since the Republic qualified for the 1994 World Cup, their success has nosedived.

The island of Ireland has had a team reach the World Cup just once in this period - when the Republic qualified for the 2002 World Cup.

They qualified for Euro 2012, where they were hammered by Croatia, Spain and Italy and scored just one goal.

Both teams reached the last-16 of Euro 2016, the largest European Championships in history featuring 24 countries.

However, in the 24-years since the Republic qualified for the 1994 World Cup, their success has nosedived.

The island of Ireland has had a team reach the World Cup just once in this period - when the Republic qualified for the 2002 World Cup.

They qualified for Euro 2012, where they were hammered by Croatia, Spain and Italy and scored just one goal.

Both teams reached the last-16 of Euro 2016, the largest European Championships in history featuring 24 countries.

The North topped their qualification group. But, under the previous format, the Republic would not have reached France as they finished third in their qualification group.

Both teams lost in the World Cup playoffs last November, albeit in contrasting circumstances.

Both teams are on course to relegated from their Uefa Nations League group when the campaign concludes over the coming days. Both face tough times in the years ahead.

The North topped their qualification group. But, under the previous format, the Republic would not have reached France as they finished third in their qualification group.

Both teams lost in the World Cup playoffs last November, albeit in contrasting circumstances.

Both teams are on course to relegated from their Uefa Nations League group when the campaign concludes over the coming days. Both face tough times in the years ahead.

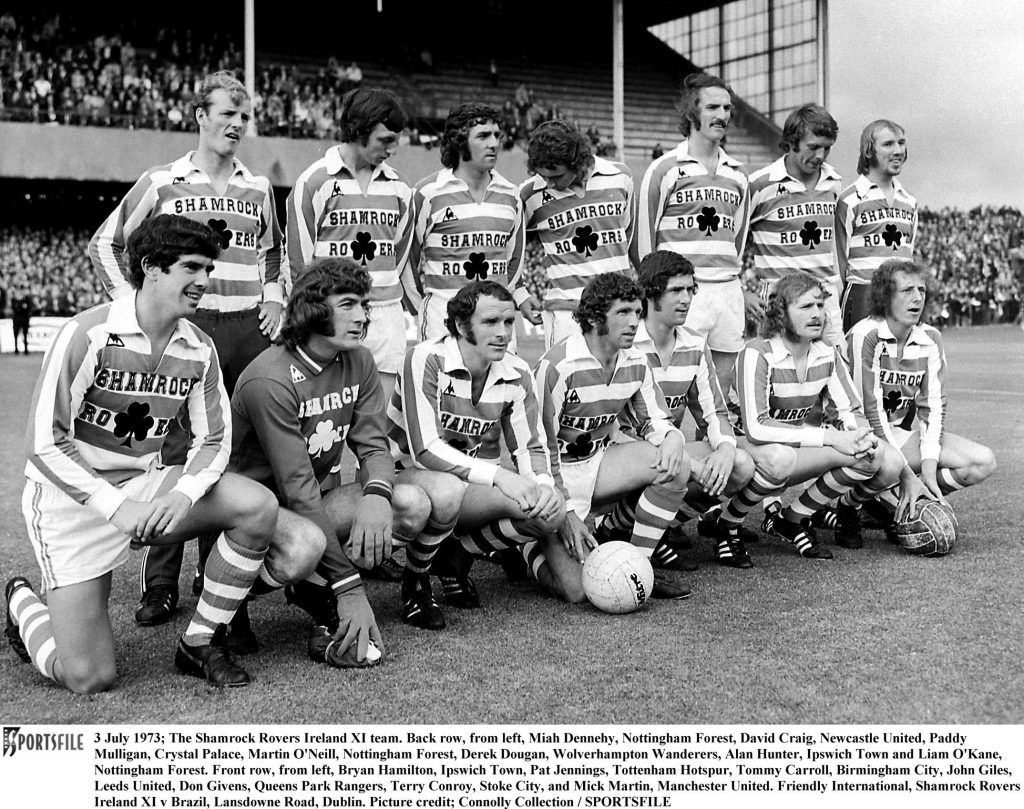

"The two associations didn't agree with the match being played," Giles said.

"The two associations didn't agree with the match being played," Giles said.

"Or they didn’t support it, but we were footballers. People like Pat Jennings, Martin O'Neill – I felt similar to them, that it was an honour to play with them."The players have always generally been in favour of a United Ireland team, particularly George Best, one of the greatest footballers to come from the island. Norman Whiteside, a Protestant from the Shankill Road in Belfast, a loyalist stronghold, was best friends with Paul McGrath, a Catholic from Crumlin in Dublin, when the pair played for Manchester United in the 1980s. If there was United Ireland team, the players would probably be the last to object to it. When it comes down to it, they're all Irish, despite coming from different backgrounds.

Ireland could be set to bid for the 2030 World Cup as co-hosts with England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Imagine a United Ireland team representing the country on home soil in a World Cup.

But the case for a United Ireland team isn't based on sentimental reasons. It's about practical concerns.

The fortunes of Irish football have declined since the game became globalised in the 1990s, as it has for several small and medium-sized countries.

The signs suggest it will only get worse unless a proactive approach is taken. Holding on to the past will consign Irish football to the past. Some radical change is needed if the island is to be competitive again on the international stage.

Ireland could be set to bid for the 2030 World Cup as co-hosts with England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Imagine a United Ireland team representing the country on home soil in a World Cup.

But the case for a United Ireland team isn't based on sentimental reasons. It's about practical concerns.

The fortunes of Irish football have declined since the game became globalised in the 1990s, as it has for several small and medium-sized countries.

The signs suggest it will only get worse unless a proactive approach is taken. Holding on to the past will consign Irish football to the past. Some radical change is needed if the island is to be competitive again on the international stage.Explore more on these topics: